What could President Biden’s troubles mean for US bonds? asks AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould, as US ten-year Treasury yield spiked after first presidential debate.

The debate over the mental acuity of Joseph R. Biden and his physical readiness to take on a second four-year term as America’s forty-sixth president is unlikely to abate any time soon, but US financial markets are not waiting to find out as they price in an increased chance of a return to office for Donald J. Trump, to match the achievement of Grover Cleveland, the only US president to lose office and then win it back,

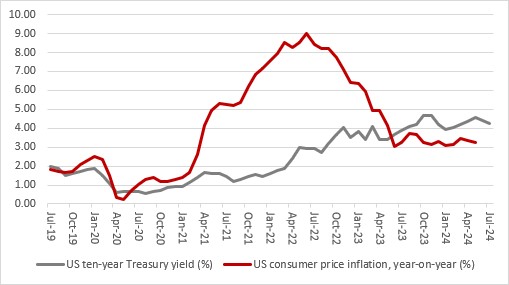

This can be seen most clearly in how the US ten-year Treasury yield responded to the presidential debate hosted by CNN late last month. The benchmark US government bond saw prices fall and yields rise sharply in response to the broadcast as fixed income investors began to anticipate a Trump win and the inflation they feared that would bring.

Source: LSEG Datastream data

Yields have since receded a little (and prices recovered), thanks to some honeyed words from US Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell, who continues to dangle the carrot of interest rate cuts, providing inflation continues to cool.

This leaves investors with a predilection for US sovereign bonds with a dilemma.

On one hand, they may want to lock in the positive real yields on offer, especially if they think the US Federal Reserve will start to cut interest rates in the autumn of this year – the ten-year yield currently exceeds the prevailing rate of US consumer price inflation by one full percentage point.

On the other, they will be wary of a reignition of inflation as that could erode the value of their carefully harvested coupons, or even erase it altogether if inflation moves above the ten-year yield on a sustained basis.

Source: LSEG Datastream data

Bond markets will be looking at the race to the White House with added concern. Three of Trump’s key policy thrusts, as outlined in the first presidential debate, all feel inflationary – namely an extension of 2017’s tax cuts, and promises of more to come (thus boosting consumer spending); more tariffs on imported goods, and not just from China (thus making goods more expensive); and moves to reduce immigration (thus limiting the growth in the pool of workers that has helped to keep US wage inflation below the levels seen here in the UK).

The tax cuts could have a further knock-on effect upon the yield on US Treasuries.

“America is already running an annual deficit that equates to around 6% of GDP and an aggregate deficit that exceeds 100% of GDP (numbers that, until recently, would have made any tin-pot republic blush with shame). The proposed Trump tax cuts would take both higher, and that assumes a benign economic environment – remember that America is racking up this enormous annual deficit when unemployment is barely 4% and the economy is growing.

The situation would look even worse, if a soft (or hard) economic landing were to transpire and tax income recedes just as welfare payments rise, as it seems logical to assume that the annual deficit would balloon. America would need to issue more debt (Treasuries) to fund itself and that could oblige the US to offer plump yields in order to tempt in buyers.

This is not to say that Biden is promising hair-shirt austerity. His first term will see America rack up an additional $7 trillion or so in borrowing (and it took from 1776 to 2003 for the US to run up an aggregate $7 trillion deficit, to give some perspective on the current rate of overspend).

Source: LSEG Datastream data, FRED - US Federal Reserve database, Congressional Budget Office

“All of this begs the question of what an appropriate level for US ten-year yields might be. The base case is the 2% inflation target. An investor may then wish to add some term premium to that, since the headline rate is stuck near 3%, thanks to strong services inflation, and is no lower than a year ago, so it may take time to return to target. Then there remains the incipient inflation risk offered by both presidential candidates. And then there is America’s massive deficit which could both pressure the Fed to cut rates to keep the Federal interest bill manageable (since it is now running at $1 trillion a year) and oblige the USA to offer tempting yields so it can find buyers for its newly issued debt.

“None of that suggests a benchmark yield on ten-year Treasuries of anything lower than 4%, which is not much below the 4.28% on offer at the time of writing. Capital upside may therefore be limited. Investors must then decide whether the coupon is enough to compensate for inflation risk, if US Treasuries are to form a part of a balanced, diversified portfolio.”