Inviting investors to buy a fund focused mainly on investment-grade credit? For the past few years this has made me as welcome as someone coughing in a supermarket at the height of the pandemic.

With yields so low, it is not surprising. But perhaps that is changing.

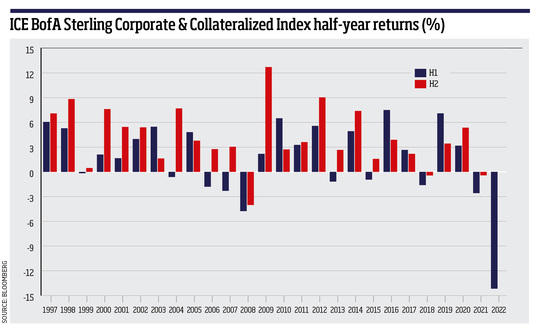

UK corporate bonds have had their worst half-year since at least 1997. The ICE BofA Sterling Corporate and Collateralized Index fell by 14.7% in the first six months of 2022. To put this into context, the previous record was a fall of 4.75% in the first half of 2008. The total return for that year was -8.58%, representing the worst full year on record. It may be of some comfort to know this was followed in 2009 by record performance of 15.18%.

Until this year, the index had never seen six months of consecutive down months. In fact, June was the seventh successive month of negative returns. Close to 60% of bonds in the index are trading below 100, underlining the extent of destruction that has taken place. The index now offers a yield of around 4.4%.

Industry in 'wait and see' mode as UK outlook post-Boris looks cautiously optimistic

What has caused this dramatic change? And have bond prices reached their bottom?

Fighting inflation

We might argue that if quantitative easing bolstered the price of risk assets over the past decade then how could the spectre of quantitative tightening do anything but lead to a reversal? But inflation is the core issue. It is difficult to argue that 10-year gilts at 1%, as they were at the beginning of the year, offered an adequate return in the context of rapidly rising inflation.

Inflation expectations continue to rise. Last month the Bank of England revised its forecast upwards - to 11% by October. Inflation is now higher in the UK than in any other G7 country. Action is clearly needed.

The Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has lifted interest rates from 0.25% to 1.25% in the course of its four meetings this year. Yet markets are currently pricing a rate of 2.8% by the year's end - 1.55% higher than today. The MPC has four more meetings scheduled before Christmas. The market is expecting it to pick up the pace of increases.

2.8% - really?

Some might argue that 2.8% looks a stretch. It is often said that the cure for inflation is inflation - it suppresses demand, which takes the heat out of the market. The UK economy appears to be contracting already. GDP figures fell 0.3% between March and April - against expectations of a 0.1% rise. The OECD has cut its UK growth forecast for this year to zero. The only country in the G20 to generate a lower forecast was Russia.

This means the balancing act between taming inflation and supporting growth is particularly tricky for the Bank. Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey recently argued that 80% of the increase in inflation was due to energy and tradeable goods, highlighting that a lot of this is beyond the ability of the Bank to control.

Bank of England: Eight major risks facing UK economy

This may explain why so far it has been cautious in raising rates. Last month three of its members voted for a 0.5% increase. They were voted down by six others who opted for the more modest 0.25% response.

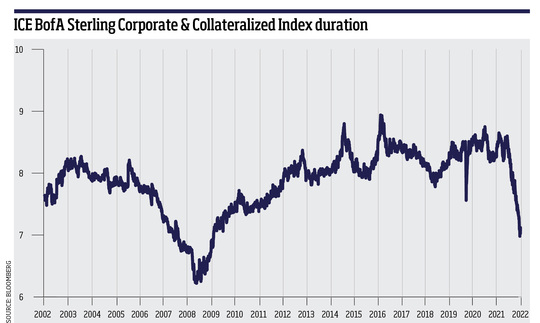

A factor to consider is interest rate sensitivity. This is the amount a fixed-income asset price moves with changes in interest rates. The sterling corporate bond index's duration is the lowest that it has been outside of the global financial crisis. This means that the sensitivity of the index to interest rate changes is the lowest it has been in 20 years, not including 2008-09.

So interest rates may not be the right cure for this problem, but they are pretty much all the Bank of England has got. It is warning that it will use that cure even if it causes recession, so important is it to tame inflation. Strong words! Bear in mind that there is a lag between a rate increase being introduced and it having an effect. In reality it may prove more difficult for the Bank of England to justify aggressive rate rises if the economic picture continues to worsen.

It is a brave call to declare the bottom of the market. Indeed, we are not yet calling it, but we are closing some of our short positions.

Fundamentally, things look bleak - persistent inflation, rising rates, slowing economic growth, war, strikes and political strife. At 200bps, the index is pretty much as cheap as it ever gets - unless we enter full-scale recession. Given fiscal support from governments, strong corporate balance sheets and low unemployment, a deep recession feels unlikely. As for the technical backdrop, bearishness is now consensus. Markets are flighty. Liquidity is not great. All these conditions could be construed as bad, but in fact these are the ingredients of a rally.

Gilt yields may still be a bit higher by year end, and the fragile liquidity could mean we dip more before we bounce. But we are surely close to the bottom.

And perhaps the most compelling indicator of this? Institutional investors are now actually inviting me to talk to them about investment-grade credit!

Grace Le (pictured) is co-manager of the Artemis Corporate Credit fund